April 17, 1833

On 17 April: Early in the morning, bright sunshine, pleasant weather. We depart early but soon receive jolts and put in off the left bank about six o’ clock to take on wood. Because of my severe head cold, I did not go ashore this early. At 7:30, 5°R [43.3°F, 6.3°C]. We are now following the left bank very closely. Here, in uninterrupted woodlands, maples, hornbeams, and redbuds are blooming, as well as Prunus [— —], which looks as though it were covered with snow. Stone reefs and boulders below along the edge of the bank. Nearby residents had fastened several fishing rods here. They were supported underneath by a thick stone.

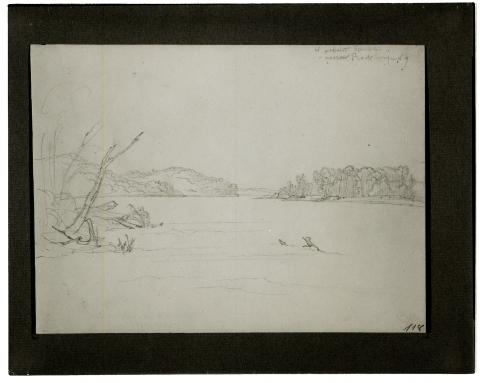

Somewhat farther, [at] about 7:30, a rather large number of ducks in a bay to our left along the forest and the sandbars. Today the banks to the left are mostly wooded hills; to the right there is woodland with borders of cottonwoods before it. To the left is an island with cottonwood and thickets already rather green.

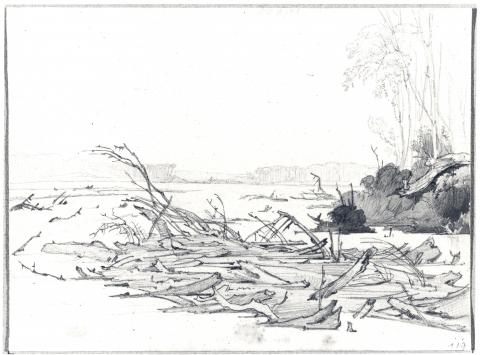

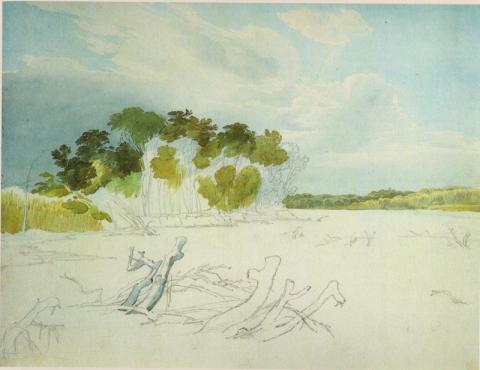

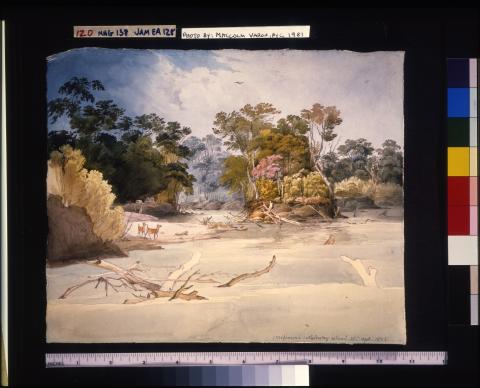

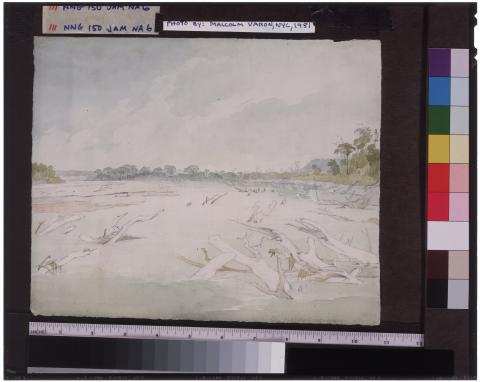

Here, at a quarter to eight, the direction of the river is W 5 1/2 S. Before us, a beautiful broad wooded island now appears; to the left opposite it, a swift brook discharges, Tabeau’ s River, which has the volume of the Fox River emptying into the Wabash. In this region our ship ran over several big trunks lying on the bottom [and] crushed and broke some of them; a huge trunk with its cluster of roots came up and writhed like a snake that had been stepped on.

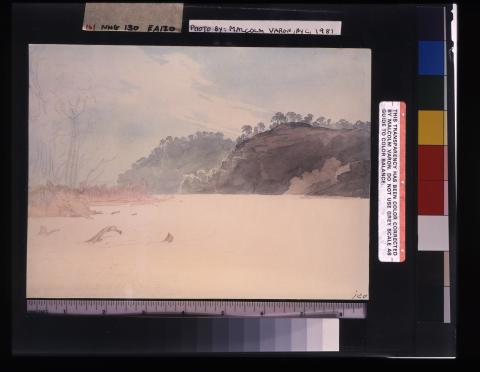

We crossed straight over to the right bank, which was so steeply eroded that a stable made of beams resting on it was half suspended in the air. It was on the point of falling into the river.  Thereupon a very bad spot followed, where we had a narrow passageway between large trunks with their jagged points lying left and right in the water. To the left, large sandbars; behind them, wooded hills. To the right, a steep bank about 10 feet high. Forest everywhere on top of it. We now ran over wood that tilted our ship to one side several times within fifteen minutes. Then we turned more to the left into the river. According to a map the Tiger River, not known to the captain, soon empties. It is supposed to empty behind an island and is therefore not visible from the ship.

Thereupon a very bad spot followed, where we had a narrow passageway between large trunks with their jagged points lying left and right in the water. To the left, large sandbars; behind them, wooded hills. To the right, a steep bank about 10 feet high. Forest everywhere on top of it. We now ran over wood that tilted our ship to one side several times within fifteen minutes. Then we turned more to the left into the river. According to a map the Tiger River, not known to the captain, soon empties. It is supposed to empty behind an island and is therefore not visible from the ship.

A paddle on one of the wheels broke; this required a short stop. A bald eagleM28Aquila leucocephala. alighted on the shore. Its nest rested in a fork of three thick branches on a tall Platanus; [this nest] was built of sticks and twigs. We assumed that there were already eaglets in it. We stopped immediately to take a sounding in the channel; meanwhile our young marksmen ran up on the bank, and shots at once rang out in the forest. The bald eagle took flight high in the sky; I made a sketch of its nest.

We now had Lexington Island before us; half an hour later, we reached a big[Page 2:20] bend in the river where, to the left, numerous sandbars lie. Close to the right bank, the narrow channel was full of tree trunks, the branches of which jutted up into the air; we made our way over several of them and soon, for the second time, moved so closely between the logs, or snags, that we brushed against them, always close to the right bank. With a writing tablet in hand, I recorded every major change during the journey, and from time to time Dougherty gave me words of the Otoe language and others, which I recorded; we smoked a large number of cigars. Today there was again warm, pleasant weather, and we could always stay on the afterdeck, where we saw the ship move over snags, one of which lifted the rudder up into the air. The ship [then] was steered obliquely across the river to the wooded hills to the left, where leaves of the mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) already covered the ground; redbuds, maples, and hornbeams were blooming. We reached a steam sawmill and several other buildings on the leftbank left bank, about half a mile inland from the town of Lexington. Here on the bank someone had built a ramp in order to pull the big clumps of wood out of the water with a windlass set up on top of the bank.

bank, about half a mile inland from the town of Lexington. Here on the bank someone had built a ramp in order to pull the big clumps of wood out of the water with a windlass set up on top of the bank.

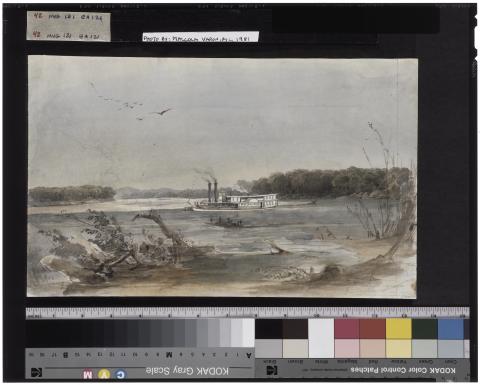

At twelve o’ clock noon, 10 1/4°R [55.1°F, 12.8°C]. When Major Dougherty first traveled up the Missouri twenty-four years ago, all this did not yet exist. People knew nothing about steamboats. The settlements reached as far as 12 miles beyond St. Charles and no farther. There was no town at Cote Sans Dessein; only French hunters had huts there for hunting. The Osages (Wassaschi), whom people encountered hunting all around here, roamed and lived in the region where Lexington is now located. A little farther upstream from the sawmill is a ferry. A house on the left bank [is] called Saw Ferry, and beyond it several houses are located in a settlement. Here the steamboat Otoe approached us. Its name was spelled incorrectly (Otto). After a quarter of an hour it passed us.

Soon afterward we reached the tip of a large island: sand with willows and behind them, cottonwoods and forest. We followed the river through a very large bend full of dangerous snags; the engine often stopped. After lunch I saw many buckeye [trees] (Aesculus), already very green, in the forest to the left along the bank. Next comes a channel, which at the edge narrowly cuts off an island and into which flows a small river, Chenay Hubert (Hubert Slew), which cannot be seen, however, from the Missouri. We followed this bank and later came upon an island to the right. Farther on, the channel runs along the right bank; to avoid a sandbar, we came so close to it that the ship brushed it and I could reach cottonwood blossoms with my hand.

After a good stretch of the river had been free of wood, we found a channel to the right of a sandbar [that seemed] interspersed with [wood]. Nowhere on a stretch of 500–600 paces did there appear more than 10 feet of space between the manifold pointed trunks, turned downstream by the current; nevertheless, the[Page 2:21] pilot twisted like a skilled coachman through these dangerous points, through which many a steamship and boat suffered disaster. Just recently Major Dougherty was on board such a ship, which fortunately was in a shallow area so that, although aground, it took only a few feet of water into the cabin. During the voyage the passengers of the Yellow Stone stood and calmly awaited the outcome of this passage. After a quarter of an hour, this place had been passed and [then] we found shallow water and touched bottom, though only slightly. [We] steered over to the left and continued along the left, or southern, bank. About an hour later we took in wood, but our stop was short. The same plants we had discovered recently and on all the previous days were blooming, in addition to a Crataegus or Pyrus, which had not yet completely opened its blossoms. We soon followed the left bank farther until we reached several islands to the right that were separated only by narrow channels. We ran aground on a sandbar, and the boat was sent out to take soundings. Meanwhile we turned back quite a distance and then sailed past the islands off the right bank, but here, too, the water was shallow. We halted and cut down long trees with which to push the ship and continued the voyage as far as toward Fishing Creek on the right bank Fire Prairie Creek and passed it on the left bank. On the right bank we halted for the night about 5 miles from Fort Osage. On the bank a huge fire was kindled that set ablaze the whole surrounding area and the tall, slender forest trees that immediately surrounded it. Mr. Sanford had gone out with a rifle and had bagged a rabbit and wounded a deer (Cervus virginianus). We had found a new tree in bloom, which seemed to me to be Zanthoxylum.