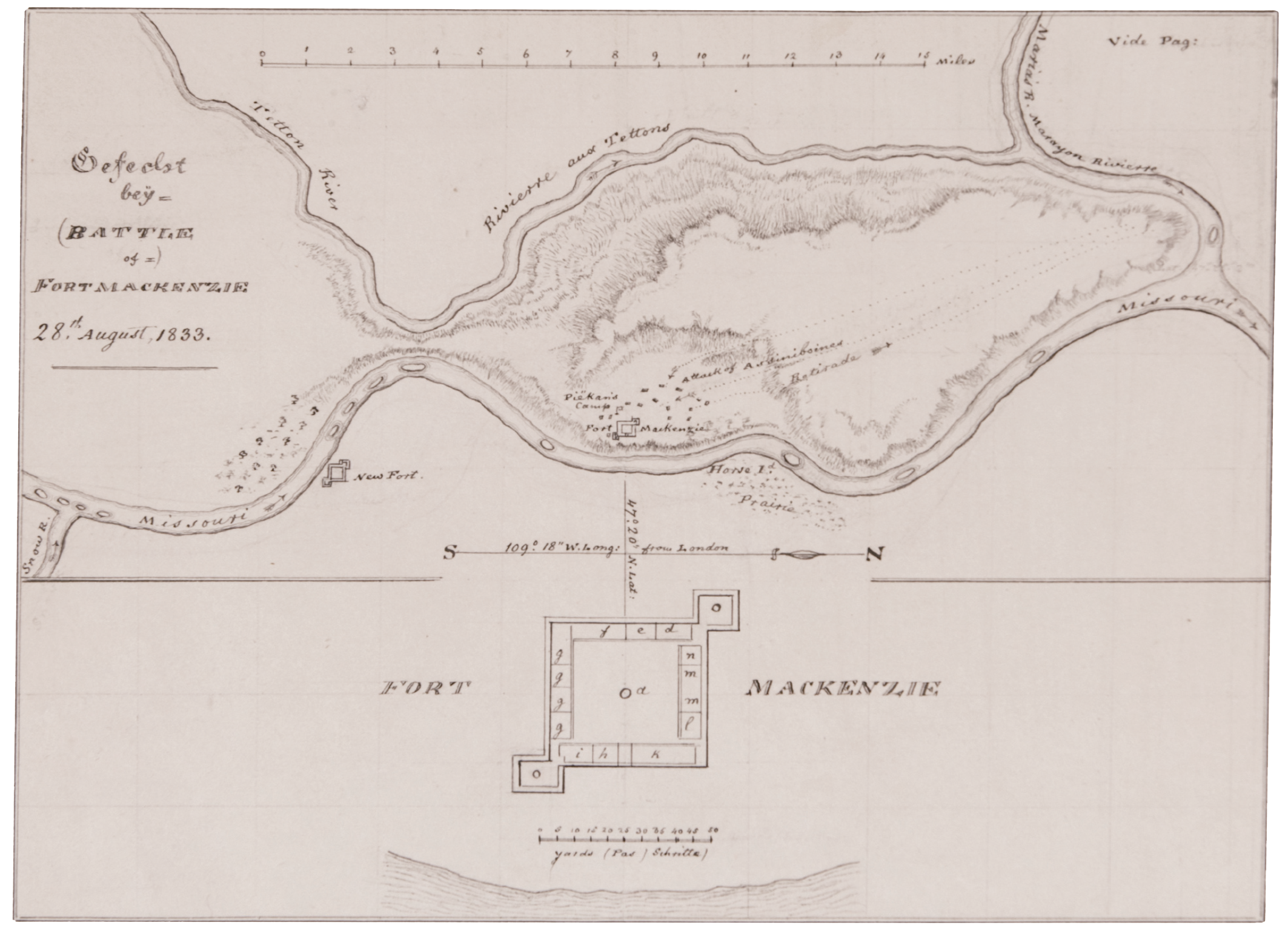

August 28, 1833

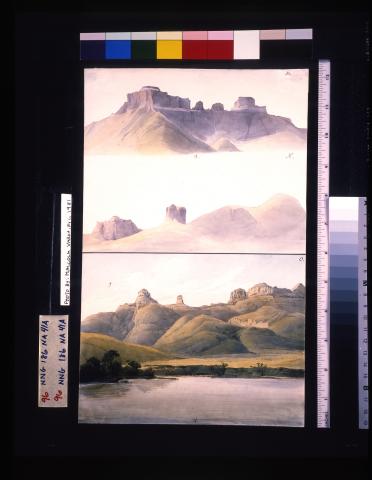

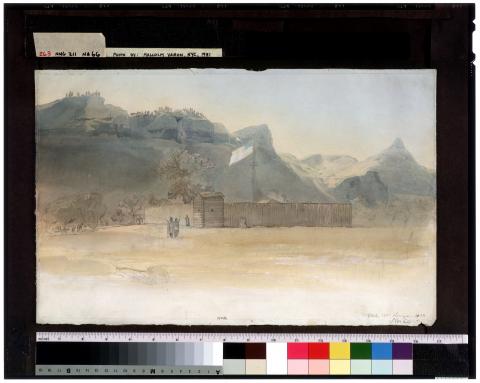

28 August: Early in the morning, overcast sky, very hot and oppressive; at 7:30, 78°F [25.6°C]. Today we had a serious alarm. There were about fifteen to twenty Piegan [tipis] near the fort and, at the most, twenty to thirty battle-ready men. During the evening these Indians had drunk much whiskey and had sung and rampaged all night. At daybreak, an Indian came running up and announced that the enemy, the Assiniboines, were advancing. Mr. Mitchell and the whites quickly jumped up, but disorder prevailed everywhere. Most engagés had neither powder nor lead in sufficient quantity, nor did the Indians. When our men climbed onto the roofs of the buildings, where there is a kind of walk along the ramparts behind the palisades, they saw, on the hills behind the fort, everything red with Indians on foot and on horseback. They quickly descended into the plain, all 580 of them, and fell upon the Piegans in their [tipis].M39The 580 enemies included 100 Crees. They were led by the Assiniboine chief Minohä́nne (le Gaucher). Since then he has changed his name and now calls himself Tatógan (Antelope).

In a moment the Indians, frightened from their sleep, fled to the fort. The Assiniboines surrounded the fort. Many bullets struck the palisade, and arrows flew into the courtyard. The women and children snatched up some of their belongings and dragged them in front of the gate of the fort; meanwhile the enemies, too, were already there, and the interpreter Berger was busy dragging women and children into the small gate while they were being shot and thrust at from behind. Between the fort and the river, four women were shot to death; another one [plus] three or four men were severely wounded, as [were] three or four children, who came into the fort pitifully injured. White Buffalo, who was constantly praised and well regarded by all, a soldier in the fort last year, had been badly grazed behind his head, and his brain seemed to be protruding into his hair. Another good Indian had an arrow shot through his arm, another one in his back—a lance wound there too—and a shot in the groin. An old man had been shot through the knee.

Mr. Mitchell had run to the gate upon the initial alarm and pulled in a few Indians. He thought the attackers were Blood Indians Piegans and called out to the engagés climbing to the roofs with their guns and rifles not to fire. But suddenly He thought those advancing were coming in a large procession to trade and were making a procession in order to firing in celebration. But when he saw the firing among the [tipis] and the wounded approaching covered with blood, he thought they were Blood Indians and still did not permit firing. Despite this, most of the engagés and interpreters had [fired]. Loretto had killed a Cree 80 paces from the fort, and bursts of gunfire were beginning [from] every corner of the fort. When all the Piegans were inside the fort, the gates were closed. Mr. Mitchell called out to the man by the cannon in the right front blockhouse to fire off a cannon [shot] against the enemy, but the last remaining Piegans were still dispersed among them. As soon as the enemy began receiving heavy fire from the fort, they withdrew somewhat, and both Piegans and whites followed them, firing heavily. Deschamps, Loretto, Doucette, and several others were exposed to the wild shooting.

We had been lying in our rooms fast asleep when Doucette stepped in, ran for his weapons, and shouted that we had to fight. While we hurriedly dressed, shots rang out from every side. Just as we stepped into the courtyard, which was filled with horses and wailing and screaming women and children, several arrows wounded a trapper, Dupuis, in the foot, and his horse in the head. Other [arrows] struck the ground. When we climbed onto the ramparts and took our positions, our guns—[including] a hastily loaded double-barrel—loaded with bird shot, the Assiniboines had already been driven 200 paces from the fort. We saw the red line of their fighters, many of them on horseback, firing individually at the fort. They withdrew more and more and finally retreated to the hills, where they concentrated in groups.

In the meantime there were pathetic scenes in the courtyard of the fort. White Buffalo, with his head wound, had such a fixed expression that I thought he would soon die, especially since he could not endure lying down.[Page 2:245] Later it turned out that he was still drunk from the previous night, and now his women, who were screaming pitifully and leading him around, gave him more and more whiskey so that he was completely stone drunk. Natáh-Otann, with his many wounds, and several wounded women and children suffered most of all. Old Ohtséquä-Stomík,M40Yellow Buffalo Bull. whose knee had been pierced by a bullet, showed me the bullet on the other side, which was cut out with my knife, [during which operation] he held up stoutly. We made use of all possible means to bind up and attend the wounded, but there is no advising the Indians. They constantly screamed and gave whiskey to the sick, only to raise their wound fever. They rattled with little bells and shook their medicines and the big bear claw that White Buffalo had hanging on his chest.

Outside the fort they had taken the scalp from the slain Cree and had assaulted him with arrows, gunshots, clubs, and stones; the women and children vied with each other [in doing this]. In particular, they completely smashed certain parts of his body and cracked his head in two. Riders had already been sent to the big camp of the Piegans, and they were expected any moment. Nínoch-Kiä́iu, Bird, and the remaining Piegans, [who were] camped farther upstream on the Missouri, had been attacked by another band of Assiniboines. Bird arrived about eight o’clock and demanded help from Mr. Mitchell. Hotokáneheh entered the fort and delivered a heated speech, whereby he reproached the whites for idly sitting around here and not going out onto the prairie to do battle with the enemy. Similar speeches irked Mr. Mitchell; he armed himself and rode out with the two Spaniards, Doucette, Deschamps, and several more men and Indians toward the prairie beyond the hills where about 150 or 200 Piegans were skirmishing with the fort’s enemy. Gradually the enemy were driven back to the Marias River, but there they made a stand and drove back the Piegans, who, it seemed, showed far less courage than the Assiniboines. Had the enemy been a little closer, they would have shot very many Piegans. Mr. Mitchell's horse received a shot high on its forequarters and fell down. He hurt his arm. Also the horse of an engagé, Bourbonnais, had been wounded; it had a shot through the neck. The rider dismounted and ran away. The Assiniboines took it, whipped it to its feet, and led it away. Here Kutonä́pi came to Mr. Mitchell and asked him about a paper he had received from the Fur Company at the last peace treaty. Mr. Mitchell replied that it was in the fort. “Oh”, [Kutonä́pi] exclaimed, “this is bad. It would have protected me from all the bullets.” When he was close to the enemy, Mr. Mitchell shouted to the Indians [asking] why they now held back, since they had said the whites did not want to fight and had no courage. Now one could see who lacked courage. Several men had remained on both sides, but they were very bad shots with their guns; otherwise, many more would have been killed. The skirmish took place at the Marias River, where the Assiniboines gathered beyond the hill and stood their ground.

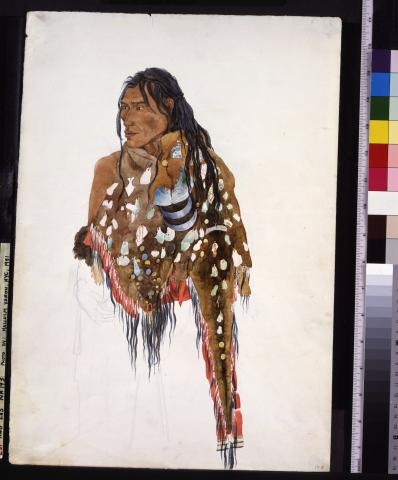

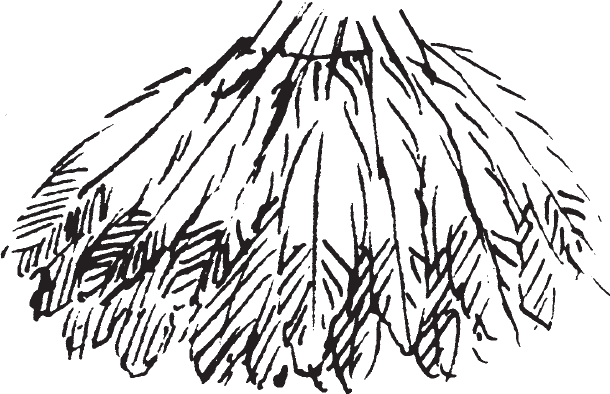

Meanwhile, at the fort we saw more and more Piegans galloping in. Many stayed at the fort; many [others] went chasing up over the hills to the battle. Some of them were very finely dressed in their war costumes: feathers hanging from their heads, their medicines fastened on, bows and guns on their backs and in their hands. They whipped their worn-out horses terribly and sang and shouted. Many of them shot the dead Assiniboine with their guns and arrows [and] stabbed and struck him so that his head was scarcely to be seen anymore and his body was charred and riddled. Because they believed they were safe now, the wounded were carried from the fort to their [tipis], where the crying and weeping continued. The [tipis] had been shredded and riddled by the enemy. A horse and several dogs lay dead. Another horse hovered between life and death. Old Pioch-Kiä́iu came to Mr. Bodmer, overjoyed, and told him that no bullets had been able to hit him; undoubtedly the reason was that he had been sketched. At twelve o’clock, 84°F [28.9°C].

Mr. Mitchell returned after one o’clock. Many Piegans had shaken his hand, praised and saluted him as their friend and fellow warrior, and given him several horses as presents, which he did not accept. After eating, Deschamps, Doucette, and several others rode out again. The Indians returned in droves and talked bravely. Altogether ten were said to have been killed by the Assiniboines. Had the latter realized their advantage, they could have bombarded us terribly here in the fort: if they had occupied the high hills, all the bullets [would have struck] the courtyard of the fort.[Page 2:246] The day was extremely hot, the fighters overheated and exhausted. All agreed that the Assiniboines had shown far more courage than the Piegans.

In the afternoon more and more Piegans came galloping in on horseback; they approached like a caravan, and the dust from their horses rose from the prairie. Many looked interesting: the naked brown men with feathers, a shield, some with a white wolf hide over their shoulder, etc. In the afternoon the Indians sat in our room, where we gave them water for refreshment and let them smoke. A man with ermine straps on his head and [accompanied by] a boy rattled his little bells before he smoked. Deschamps had recognized the hostile Indians as Assiniboines and Crees. They had recognized him and called out to him; he did not disclose his identity, however, and killed several of them. He had thought a Piegan woman hiding in the thickets by the fort was an enemy and killed her by mistake. Among the slain women was the daughter of Old Stiff Leg, Haiesikate, who lamented bitterly and shrieked. The loss of the Piegans cannot yet be completely determined.

Toward evening several men returned from the Marayon [Marias River], where the enemy was still being observed. By now the Piegans had gradually been reinforced so that they were as strong as the Assiniboines. They had shot to death several more of the latter but also had a few [of their own] wounded—severely so, in the case of a handsome young man. We went into the [tipis] and bandaged five or six of the wounded with the use of ointment, had them washed, [and] cut off their hair around the head wounds. Instead of whiskey, which they always drank when they had wound fever, [we] brought them sugar water, for they like sugar very much.M41A wounded child had died. Its face had been painted red with vermilion. The whole courtyard of the fort was filled with Piegans. Some of them had stayed here all day to give full rein to their courage. The evening was very pleasant.

Our fighters and many Piegans returned; Deschamps had been in serious difficulties. When the Assiniboines rushed forward, the Piegans left their posts; and when he called, two came back, including [— —], who always pretended to be my friend and followed me like a shadow. He caught another horse for Deschamps when he lost his own, and thus he escaped. As I was standing in front of the fort, several Piegans returned in very fine costumes. One of them had an exceptionally beautiful feather ornament [like] a feather bonnet hanging down his back, which he had received from the Crows. He was a handsome man and especially well dressed. My friend OjibweM42His name is [——]. and many others pressed toward us. The first two wanted to sleep in the fort. Those returning announced [that] they had encircled the enemy and would attack them the first thing in the morning. We think the latter will not wait for morning but will withdraw during the night. The mutilated corpse in front of the fort had been burned. On the inside and all around, the fort was filled with Piegans. One heard talk of nothing but the events of the day. Everyone related his deeds and what had happened to him. The script of the day was written on everyone’s brow. The Indians were tired, hungry, and thirsty. They demanded whiskey; they were given water. Mr. Mitchell was tired, too, and took a [good] rest.

pretended to be my friend and followed me like a shadow. He caught another horse for Deschamps when he lost his own, and thus he escaped. As I was standing in front of the fort, several Piegans returned in very fine costumes. One of them had an exceptionally beautiful feather ornament [like] a feather bonnet hanging down his back, which he had received from the Crows. He was a handsome man and especially well dressed. My friend OjibweM42His name is [——]. and many others pressed toward us. The first two wanted to sleep in the fort. Those returning announced [that] they had encircled the enemy and would attack them the first thing in the morning. We think the latter will not wait for morning but will withdraw during the night. The mutilated corpse in front of the fort had been burned. On the inside and all around, the fort was filled with Piegans. One heard talk of nothing but the events of the day. Everyone related his deeds and what had happened to him. The script of the day was written on everyone’s brow. The Indians were tired, hungry, and thirsty. They demanded whiskey; they were given water. Mr. Mitchell was tired, too, and took a [good] rest.

Beleaguered by Indians, I used the evening to record the events of the day. During the afternoon, too, one had again heard several enemy Indians talking and thus realized that they came from the north. Bullets [shot at us] were said to have had much harder lead than our own, from which one drew the same conclusion.[Page 2:247] When night fell, the Indians in the mess hall were given something to smoke; one of our pipes, too, circulated among them. Although I lent it very often, it was nevertheless always returned again. Many had no pipes; usually one finds only one or two in every [tipi]. Mr. Bodmer’s music box entertained them enormously; they stared at it in astonishment. Thunderstorm during the night; thunder and lightning in the southwest.