March 7, 1834

7 March: In the morning, gray sky; cold; the whole area covered with 2 to 3 inches of snow. at seven thirty, 11°F [−11.7°C]. Wind west. At eight thirty the sky was clearing; bright sun, much glare [reflected from] the snow. Cháratä-Numakschi and a few other Mandans [were] in Kipp’s room; at our place [were] the Arikara, who was being drawn, and Máhchsi-Karéhde. At twelve o’clock noon, 28°F [−2.2°C], wind northwest. In the afternoon it snowed heavily again. I had to draw a bear for the Arikara and a hussar for Máhchsi-Karéhde. The Arikara wanted to have something like a forest on his picture, which I assured him I was not able to do. They then said among themselves [that] the tree [must] be my medicine [and] Bodmer took over.

Crazy Bear wanted to have himself drawn [but made us] wait for him four to five days. This afternoon he came, very well dressed, but was told [that] the Arikara was being drawn now and it would be too late in the afternoon. He answered that, in that case, he did not want to be drawn at all.

About evening the Dog Society (Meníss-Óchatä) from Ruhptare danced at Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch. Bodmer went there. They were assembled in the medicine lodge when Mató-Tópe entered very proudly. He belongs to this society in his village. He did not look at Bodmer at all, even though he visited us frequently; [he] proceeded to walk straight past him. Síh-Chidä (who also belongs to this band in Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch) entered and fired his gun in the lodge.

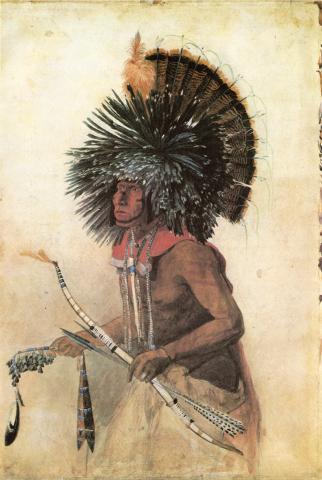

The evening was gray, overcast with snow clouds that, however, broke up in the west; it snowed very fine. Suddenly the Meníss-Óchatä from Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch marched to the fort, [and] a crowd of people swarmed around them. [From] outside the gate, we heard the frequently repeated [sounds] of their war[Page 3:56] whistles. Twenty-seven to twenty-eight men closed the circle. All of them were dressed in their best—some in beautiful robes, a few with bighorn shirts, others in red cloth shirts or European uniform overcoats, yet others with bare upper bodies on which [their] coups and wounds were painted in reddish brown. Four of them—these are the leading, or real, Dogs—wore enormous bonnets or caps on their heads, [which hung down] far below their shoulders: giant tufts of densely arranged raven tail feathers [with] small down feathers attached [to each raven feather] tip. In the middle of [each] mass of feathers, the beautiful white and black tail of a war eagle stood upright, attached in a line reaching from front to back. When they dance, all these feathers rock up and down. Two other men wore bonnets just as enormous as [those of] the real Dogs [but made] of yellowish, reddish, dark, horizontally striped eagle owl feathers, and one wore the large, beautiful máhchsi-akub-háschka. All others wore on their heads a thick tuft of eagle owl, raven, and magpie tail feathers. Only the men with the enormous feather bonnets wore horizontally across their chests strips of scarlet cloth that ran back over both shoulders and were tied in a knot at the lower back, from where they hung down to the calves. These are the real Dogs. If someone throws a piece of meat in the fire or on the ground and tells them, “There, dog, eat!” they must set upon it right away and eat it raw.

One of the men had attached the tail of a wild turkey to the top of his large bonnet of eagle owl feathers. At their necks they all wore their war whistles; in their left arms, their weapons: guns, bows, and the like. In their right hands, they [carried] the chichikué [that was] designated for this society, part of it decorated with blue and white rassade and completely festooned with animal hooves. From the tip [of the rattle], a single war eagle feather is usually hung, either left white or tinted red. They set a larger drum on the ground in the circle (mánna-berächä́). Five poorly dressed, seated men beat it. Beside them stood two additional men, each one beating a small drum similar to a tambourine. The Dogs accompanied the intense, rapidly repeated drumbeats [with] their war whistles, [blowing] short, repetitive notes or tones.

Then they suddenly began to dance. They dropped their robes behind them on the ground. Some danced in the center of the circle, with their upper bodies leaning forward, jumping up from the ground a little, with their feet held equally apart, and then stepping down hard. The others danced around them in no particular order, facing the inside [of the circle]. They were mostly crowded rather close together, and once in a while they all lowered their heads and upper bodies even more together while whistling on their war whistles; the drummers beat concurrently [and] intensely; all the chichikués were rattled at the same time. The view was extremely novel and strange. At the same time laconically The many headfeathers bouncing up and down, the wild noise, the whistling, drumming, the colorful, diverse masquerade—a noteworthy scene for a stranger! These Dogs had purchased [their positions] from former society [members] and had to offer their wives on this occasion to their so-called fathers (from whom they buy), just as [is done in] all the societies or dances.

In the evening the weather was cold; a very fine snow fell. The sky was very densely and darkly overcast.